Episode Transcript

Speaker 0 00:00:00 But, uh, Richard, we're glad to have you. Um, we, uh, are gonna jump right in, uh, you know, the insanity of modern monetary theory. Um, I'm very interested, uh, I have, uh, somewhat of an idea about it from, uh, you know, 20 years ago. But, um, I'm interested in, uh, your take and we'll be taking audience questions and just, you know, what is modern monetary theory and, and what makes it, uh, insane?

Speaker 1 00:00:28 Yeah. Thanks Scott for, uh, hosting this and thanks everyone for joining. Uh, bear, you have to bear with me a little bit. I am battling, uh, bronchitis, so I might cough every once in a while. Goodness. However, here's the topic and why I think it's important. Um, we're in a, a mode now, and not just in the US but globally, where overextended welfare states and not, not due just to welfare, but also to war spending. Uh, the, the deficit spending is enormous and deficit spending is defined as spending not financed by taxation. So, just to go back to basics, to set the context for mmt, well, I'll keep calling it mmt, modern monetary theory. Um, there are three main ways to finance government spending, whatever the level is. Taxation is the most well known, but governments can also borrow. And then in the modern times, they print money cuz they have a monopoly over the issuance of base money.

Speaker 1 00:01:32 So that hasn't always been true, and that's not a capitalist system, that the fiat money system, fiat literally meaning legal tender. You must accept, uh, and use the government's money. Um, and uh, so those are the three, uh, forms of financing government. And it should be obvious in a Democrat setting that taxes are risky. Electorally it, it's hard to win elections saying, I want only know, not, I only want not only more spending, but financed by taxes. So if you can somehow get this spending, which is an electoral boon, uh, without people knowing or feeling the pinch of how it's paid for, that's ideal. And so there's a built in bias, I would say, a bias in unrestrained democracies. By that I mean the government is not consciously constrained at all. Uh, there's a, a bias toward fiscal profligacy. So unrestrained democracy breeds fiscal profligacy.

Speaker 1 00:02:37 So the, the kind of chronic deficit spending and debt buildup and debt accumulation that we're seeing is due to this bias. And it's, and it's a severe to varying degrees in various countries. Now, there's something called fiscal illusion, where, as I said, if you don't feel the pinch of taxation and instead government borrows, well, you, you voluntarily, at least so far, people voluntarily lend to the government. It's a bit bit technical here, but technically they buy US bonds or t or t-bills. And so that's not, uh, involuntary in the sense of taxation. So it isn't felt, uh, by the taxpayer, I should say also that even in the tax consequence, the, the, the tax burden and incident has been shifted so much toward those who make more money. That roughly half the population, for example, in the US doesn't even pay net net a federal income tax.

Speaker 1 00:03:35 So the whole, the whole goal and point of a graduated income tax is to shift the burden of the tax burden to a smaller minority of people who you can outvote. Now. Now inflation, uh, I've had an entire clubhouse set, uh, on inflation, uh, for uh, t a s. So you can go back and look at that, but inflation is a decline in the value of money. And a decline in the value of money means an increase in the cost of living. You have to use more pieces of paper to get the loaf for bread. Now, that is typically blamed on the bread seller, the grocer, the gas station owner. And people do not think of, wow, I'm paying a higher price for gas cuz the Federal Reserve did it. And the Federal Reserve did it cuz congress deficit spent and the Fed had to, you know, print money to help Congress pay for its deficiency.

Speaker 1 00:04:29 Um, so you see how an here's another way that the problem is deflected or the the symptoms are, are, are showing up outside of government. And of course government stokes this by blaming greedy price gouging, uh, gas station owners and other things like that. So just that just sets as a general context. I just want to set that up so people understood the kind of like the basics of public finance and why the, the funding sh mix, if you will. If you thought of it as a pie chart, what part of government spending is being supported by, uh, tax revenues versus borrowing versus money creation? Now, modern monetary theory, uh, this may not surprise you, is is neither modern <laugh> nor very theoretically sound, but, um, it, uh, is pitched as something like that, right? So, uh, let's just look at its origins. The, uh, the great Austrian economist, the one who actually started the Austrian School, Carl Manger, uh, you can easily find this on an internet, wrote it on the internet, wrote a fascinating, wonderful, very influential, actually essay called The Origins of Money 1892, uh, right in the middle of a fairly pro capitalist or the tail end of a pro capitalist century.

Speaker 1 00:05:51 And his view, and I think it's the right view, is that money's origins are market based, that over the years, not to get into a history of money here, but that money has an objective basis, that it comes out of barter. That the things we barter, the commodities and goods that we barter are real, tangible goods beneficial to our life. But if you're going to get beyond barter to indirect exchange and the great efficiencies associated with that, you need a quote, medium of exchange so that people aren't trading, uh, goods against good but goods form money. And then you use the money to buy goods. It's an enormously important increase in productivity, um, enabled by that kind of system. Now, manger showed and history confirmed that people converged on the precious metals as money. And here I'll just include gold, silver, platinum. It was mostly gold because of its objective features.

Speaker 1 00:06:51 In other words, nothing mystical, nothing arbitrary about it. Uh, of course you don't eat gold, you don't eat silver. That's exactly why they're so good as a medium of exchange. They're durable, they're easily divisible, they're easily transportable, being precious. They have a high value per ounce. Uh, so for various reasons, uh, manger shows that convergence on gold-based money was objective, was rational, was market-based, was egoistic, was profit oriented. Profit oriented, by the way, in the sense of the banks serving as holders of money. Uh, you would wanna hold your money in safe deposit, right? But then also you'd be motivated to let them lend your money so you can earn interest. And so banks would not only store and hold and exchange your precious rentals for you, but start lending them out. And of course, more convenient things like currencies, checking accounts, uh, what we see today with debit cards and things like that.

Speaker 1 00:07:52 But their derivatives made valuable by the fact that they're convertible into base, the base money, the golden silver money. Now we've been off the gold standard for status reasons, not for market reasons, for many, many decades now. It began around World War I, it accelerated during the Great Depression, but the final links were broken in 1971 when the Breon Woods School Exchange standard went away. Now again, this is as more background. And now I'm gonna dig into mmt. MMT denies, uh, the manger origins of money argument. The modern monetary theory leverages off of a book from 1905, actually, that's how modern it is by a fellow named George Naapp, K N A P P a, German not, uh, not translated into English till 1924. But naps view was that the state, state power, the state monopoly state legal tender laws are what makes money money.

Speaker 1 00:08:59 Now, if you said to him, well, isn't it true that, um, manger story is correct? And just the fact that government has co-opted money has taken over, say, an existing monetary system that the markets developed, uh, that's very different from, you know, rejecting manger. You're just saying, well, once, uh, the markets produce something, governments can seize it. No, na actually insisted that even in the case of gold money, any kind of money, whatever, uh, unless there was a state forcing its ways upon people basically making them use it, uh, money would have no credibility. So, um, there were many others besides an app who contributed to this, uh, kind of argument. Uh, sometimes it's also called the credit theory of money, or the debt theory of money. And again, the idea is money has its value, not because it's anchored in metals, not in real commodities, but in these financial instruments called debt and credit and specifically government debt.

Speaker 1 00:10:02 And, uh, on the grounds that government debt is least questioned, it's the safest, it's the least prone to defaulting. And why? Cuz it has a power to tax. See if your debts become excessive, if your credit card balance gets too much, you can't go, well, not legally yet, and steal money and pay down the balance, but the, uh, extent that the government, uh, can tax it's felt that, well, it can always get tax revenues. So that is one of the arguments, uh, that MMT adds to the mix and says, um, we're gonna give you here a state, I would call it aist, a theory of money. Now, here in present times is the implications of this and why they're so important. It generally, MMT is arguing the following. Now, think about this. If you know anything about economics one-on-one, 1 0 1 and supply and demand, their view is that in today's context, with no convertibility of money into anything with fiat power behind it, and even with this massive deficit spending, governments, uh, can issue money virtually without limit.

Speaker 1 00:11:15 And here's the key part, virtually without negative consequences. Now, what would the negative consequences be of issuing too much money? An extra supply of money not followed up by demand would lower the value of money. Just like an extra supply of shoes not demanded would lower the price of shoes. Well, lowering the value of money, that's what I said earlier, is lowering the purchasing power of money. That is what inflation is. It's inflation is the higher cost of living, which is a symptom of a decline in the value of money. Well, the mmt people are saying no, there isn't any, um, objective material, substantial, however you wanna put it, limit how much, um, money governments can spend without causing, uh, higher and sustained inflation. Okay, that's 0.1. And remember, that's the third four form, or the source I should say, of financing, government spending, the inflation, the money creation.

Speaker 1 00:12:13 But they also contend this. Now listen to this, the government can also issue debt without virtual limit. They can issue bonds, they can borrow, in other words, virtually without limit. And again, the the punchline without deleterious effects. And what would be the deleterious effects of borrowing too much higher interest rates. Again, a little bit technical here, but all else equal. Uh, the more you borrow, the more you issue bonds all else equal, the more the bond prices would go down, just like the value of money goes down. And in math, in bond math, bond prices going down is equivalent to interest rates going up. So now consider this, we're talking now about the two out of the three methods of financing government. And the m t theory is you can print verse money virtually without limit and without negative effects. And you can borrow virtually without limit, without negative effects.

Speaker 1 00:13:12 This is, as you can imagine, to a politician, the to the ear of a politician. This is Harry Potter, this is just the magic wand. This is wonderful <laugh>. Cause if you're, if you're telling us that we can continue spending crazily and we don't have to tax people, and we can just resort to these other methods, other methods, which have already been demonstrated to have been part of fiscal illusion where people have no idea of what's going on, that is just golden. And that is just golden. So the MMT people are popular, becoming popular, becoming more popular, the more fiscally irresponsible the US and other countries be, uh, have become. Now I, I'll leave this to the q and a and others who wanna dig into this more deeply, but it's not completely out of the blue that we've gotten m m t theorists and, and by the way, I shouldn't mention, but those who want name, I'll name names that probably the most publicly prominent one is Stephanie Kelton, k e l t o n, I think she's at Stony Brook University.

Speaker 1 00:14:18 Uh, some of her stuff is published under her maiden name Stephanie Bell. But another one is Warren Mosler, m o s l e r. And a third one is Randall Ray, w r a y. So they have articles and essays and books out there. And, and so it's grounded in, um, this, as I said, this earlier work, 1905, that's more than a century ago from George Naapp. But I must also say that I'm not sure the Mmt people would be so, um, influential today. And I'm not saying they're dominantly influential or don't have any critics, even outside the Austrian economic camp. Uh, they do, especially as you can imagine among Monetarists. Uh, but they would not have been possible without the Keynesian Revolution. And it was Kanes, if, you know, in the twenties and thirties, who began a British economist who began a critique of capitalism and financial markets and the gold standard and free trade, uh, to the point where, where it really ruined modern economics.

Speaker 1 00:15:23 But unfortunately, incorporated in mon economic textbooks. 14 editions of samuelson's economics textbooks, Samuelson, the m MIT economist taught hoards of, uh, students, future policy makers, future business people, the Keynesian model, which is anti-capitalist. And from, from every, uh, dimension you can imagine, m n t gets, uh, support and solace from the keynesians. Now, there are some Keynesian critics of it, but, but I think without the Keynesian model, there's no way the m t people would've, uh, had a foothold. They would've been dismissed as monetary crank. We used to call monetary cranks. People who basically think that you can create wealth, I mean, real wealth by printing money and borrowing to be clear, even in a capitalist setting, money is, but a representation of real wealth. I mean, it is wealth in the sense of gold, but its main purpose is to represent an exchange and facilitate the exchange of wealth.

Speaker 1 00:16:27 And it's also true of borrowing and, and the debt instruments associated with borrowing. You're borrowing existing wealth, you may put it to use to create other wealth, but simply the idea of without limit printing money convertible into nothing or issuing debt without providing for its repayment is not a way to create wealth. In fact, it gets in the way of creating wealth. So, um, the Keynesian system has had its ups and downs, its most downs, thankfully, in the last 20 years of the last century. So in the eighties and nineties, Keynesianism was in retreat. And what was the alternative? Not Keynesian demand side consumptionist, uh, economics, but supply side, entrepreneurial growth oriented economics of the Laffer, uh, Mundel Reagan variety. Unfortunately, in the 2008 financial crisis, Keynesianism made a comeback. Marxism made a comeback, woke generally has made a comeback the whole, the whole, uh, 20 years, I would say mostly since nine 11.

Speaker 1 00:17:39 The trend in the last 20 years has definitely been anti-capitalist. And that is yet another reason why the MMT people are being elevated. Even as an economist, I have never believed that economics is a primary or that economic policy making is a primary. I mean, in the sense of the main driver of a culture or people, it's always philosophy. And then it shows up in culture and politics. And politics looks for the economist. It wants, if we were living in a freer age, if we were living in an age of fiscal rectitude and government, uh, restricted to its proper functions, the most prominent economists would be advocates of the gold standard advocates of free banking, uh, advocates of sound policies and taxes, trade and elsewhere. But if this trend is status, they will look for status monetary advisors. So these advisors come in as side a kind of like justifiers, uh, cover, uh, for really irresponsible behavior. So I'll stop there because, um, it's about 20 minutes, minutes into it. That's about my, the limit I wanna impose on myself and leave it open to questions and comments.

Speaker 0 00:18:53 Okay, great. Well, uh, we wanna encourage people to come up with questions. Uh, David, I know we were having some issues with your sound earlier. Uh, I didn't know if you wanted to try to get a question in. Um, but, uh, if not, we can, uh, go to Connie. Connie, thanks for joining us.

Speaker 2 00:19:13 Well, hi there. Thanks for having me up. This is always one of my favorite highlights of the week.

Speaker 0 00:19:19 Good. Um, uh, Richard, I, um, I just wanted to ask, there, there's a name, you, you brought up some names that, uh, there's, I always associated mm mt with like a Thomas pick Pickety, or maybe it's just left wing economist, or

Speaker 1 00:19:39 I would, I would, I would not put Pickety in there. I've written on, uh, Thomas Pickety, he's a French economist, but he's a Marxist. And funny enough, the Marxists, um, bad as they are, are tend not to fall for this kind of stuff, <laugh>, but, but only because they're materialists. And so they're suspicious of anyone like the M mmt people who claim that paper or nominal, uh, parchment type things can create real wealth. No, the, the Marxist view is physical, muscular labor, you know, in manufacturing on an assembly line is the sole source of wealth. And, um, you know, you know, to the point where white collar workers or intellectual labor is considered parasitic. So, uh, spaghetti, I wouldn't, uh, spaghetti is definitely not part of this m t crowd, um, but certainly shares the anti-capitalist Ben Kelton, by the way, Stephanie Kelton, um, one of the ones I cited, uh, was, was, I still think is an economic advisor to Bernie Sanders. So quite apropo, all these people tend to be advisors to really bad folks, A A O C Sanders, all those, uh, to the most anti-capitalist side of the eye. And

Speaker 0 00:20:59 Donny's advising Biden

Speaker 1 00:21:01 <laugh>. Um, yeah,

Speaker 0 00:21:04 Um, well, I, you know, it was, uh, Peter Teal that said that we're in a race between technology and, and politics. I mean, is it because technology's been increasing productivity that it absorbs some of this extra spending and, and, you know, highs the consequences?

Speaker 1 00:21:23 Well, that's a really good point because, um, one of the things I could have said in the opening is if you look at, uh, I suppose I was an MMT person, let me give the best argument I could, at least empirically I'll say, will you claim that we think, uh, money can be increased enormously without deleterious consequences? Well, if you look at the charts, the money has been increased enormously. The money supply in the US has boomed in an unprecedented way in the last 10 years. It's just literally off the charts. Where's the inflation? That's what they'd say. They'd say, well, there is inflation. It's slightly higher inflation, but it's not even the inflation of the Carter years where when it was one or 14, 15%. So inflation got up to 10% recently. But, you know, pretty much over the last decade, inflation, you know, as they define it, increases in the consumer price index has been something like two or 3% a year.

Speaker 1 00:22:20 So they would cite that as a reason to say, see, we're right, we're right after all. And if you say, well, uh, pretty soon the deluge, you know, it's, it's coming. Eventually, they'll say, okay, eventually, but the every, with every passing year that goes by, you are wrong, wrong, wrong. Now notice they would say the same thing on the debt. The US debt now is approaching 32 trillion. Uh, if you measure it relative to gdp, it's something like 125% of gdp. D how high is that? It's the highest ever in US history since World War ii. So it was 125% in World War II when the borrowing was massive during that war. Um, but it got all the way down to 35% ratio in 1975 or so. Well, again, this ratio has increased enormously. So not only is the debt, you know, doubled just in the last eight years from 1516 to 32, but this ratio to GDP to national income has increased.

Speaker 1 00:23:18 But the MMT people would say, look out at the data, what would be the sign of trouble? Higher interest rates. And they would say, we don't have higher interest rates. Yeah, they've gone up a little bit. Uh, the bond yield for the US is, I don't know what the 10 year bond yield last time I checked is near 2.83%, 3%. They would say in the Carter years it was 16, 18%. You see, so they, they're in a, a kind of a sweet spot situation where they can say, we have increased money enormously without inflationary, uh, consequence, and we've increased borrowing enormously without bad consequence. And by the way, in each case, when they talk about increasing money, the mmt people say, what's the big deal? That just increases your income? So they treat government printing of money, you know, they'll say the, when the money has to go somewhere, they go, they put it quote into the economy, it ends up in people's pockets.

Speaker 1 00:24:18 Their view is it's an enhancement into people's income in the private sector. And then on debt, they would say, okay, so we've issued debt. So the US government borrows, borrows, borrows, borrows. But they would say, if you look at it from the flip side, they're assets. They are assets. <laugh>. If you, if you go to the bank, if you go to an insurance company, if you gotta an investment fund, what are they holding as assets, as interest earning assets? Treasury bonds, treasury bills, treasury notes. And so from a certain perspective, it's true that those are assets. The question is, how are the assets, uh, serviced? If a company borrows money or even raises money in the capital markets as equity, they're investing presumably in productive enterprises, right? So the source of repayment comes from actual production, whereas the government is not doing that. The government is not printing money or borrowing money in order to go produce things to generate income and then service the debt.

Speaker 1 00:25:21 We all know that. Um, increasingly the whole point of the welfare state is not to promote the creation of wealth, but the transfer of it from Peter to pay Paul. In other words, the redistributive state, the state that says inequality of income and wealth is terrible. We're gonna take it from those who have give it to those who do not have, even if we have to print money and borrow accordingly. Well, that isn't the multiplication of wealth, it's the division of wealth. So you don't, you don't multiply wealth by dividing it. And so, uh, that's another reason to, to call this into question. But my theory, Scott, it's not technology. My theory as to why you can have cascading supplies of money and yet no inflation. Well, the other side is the demand. It's not just the supply of money, but the demand. And if you have a severely high demand for money, sometimes, by the way called hoarding, imagine what kind of economy that is.

Speaker 1 00:26:19 An economy where people say, yes, a lot of money supply is being created, but I'm gonna sit on it. I'm gonna hold it. I'm gonna remain very, very liquid. I'm not gonna invest this. That's a fearful economy. That's an economy that's not vibrant, not growing, not entrepreneurial. And I would say the same thing about government debt. The paradox of how can they issue so much debt, uh, in supply, you know, and yet the interest rates aren't going up. It has to mean that there's a great demand to hold that debt. That is just the, the nature of s law, supply and demand. Okay? Now imagine if that's true of all the financial instruments you could hold and, and hold dearly and hold, you know, in great demand. You could pick government bonds, but you could also pick corporate shares, corporate bonds, uh, uh, real estate, other investments.

Speaker 1 00:27:15 The fact that people on the investment spectrum would prefer to hold government debt on the grounds that it's safe and can't default again is a kind of risk averse, a very stagnant kind of economy. And, and that I would say is, uh, a, a signature of what excessive government spending, printing, and borrowing can do. People are always looking for a day of a crash, uh, a day of a very dramatic everything collapsing. And you can have days like that. But what's less understood is that there is a slow drip, drip, drip of stagnation and erosion and undermining that goes all as that goes on as well. It's less known, it's less observed, it's less dramatic, but nonetheless, still can go on for years and decades where you're just stagnating. And Japan has felt that Japan, whose debt ratio now is something like 240% of gdp. Again, they still have low inflation, they still have low interest rates, but that is a stagnating, uh, dying economy. Uh, people getting older and older. Uh, there's no future for people. It's a total stagnation. So economists refer to as the lost decades in Japan, and that's what the US risks, if it keeps down this road. So the paradoxes here can be, um, uh, understood, uh, if you dig a little deeper.

Speaker 0 00:28:42 Good stuff. Well, uh, let's go to Peggy. Peggy, thanks for waiting.

Speaker 3 00:28:47 Um, I don't know how to, can you hear me? Yeah. Oh, okay. Good. <laugh>. Um, Richard, really well stated, and you already addressed some of the things I was thinking of as a question, one of which in terms of how to, I don't know, message this differently. Yeah.

Speaker 3 00:29:05 There was a way to measure the incredibly deflationary effect of the technology, especially that's been exponentially rising the last few decades, and how much hidden, um, how much the government has been able to skim without us noticing and therefore deprive us of the buying power of our dollars. Um, could that be something of a convincing message? Um, and I also, I'm an, I'm an investor. And the irony, as you say, the paradox is that the more they create this risky environment, the more people you know and the higher inflation, the more people are seeking government bonds because they're guaranteed kind of by fiat. But that's the very thing that making the whole thing so unsafe to begin with.

Speaker 1 00:30:01 Yes. Very good, very good points. Um, let me address two things I'm hearing you say, um, great questions, Peggy, but the, the se let me go to the second one first. It, it's true that, um, when people say, well, the government bond is safer, say than the corporate bond there, they're talking about default risk. And it is true. And here the mm m t people are, are onto something. And this is undeniable. I would even admit it. If the government has a monopoly fiat powered to issue money, technically yes, it will never default on debt, cuz it can always print the money necessary to pay principle and interest. But I think we have to realize that inflation itself is a default. So, so the so money itself is issued by the government and you have to, I think you have to admit honestly that if it's issuing something and it's losing value, that that is a kind of default, especially when compared to when we were on the gold standard and the purchasing power, the dollar held steady.

Speaker 3 00:30:59 Yes. And especially the longer term the debt is, yeah, the more, the dollar that you're getting paid back a small fraction of what you lent.

Speaker 1 00:31:08 So it's, okay. So the difference here between a government bonds and a corporate bonds, the corporate is prone to say, going to bankruptcy court and you lose money that way. But they're both prone to, uh, inflation risk in both cases. The corporate pond is paying you dollars that are deteriorating in value over time. But, and so I just wanted to make that distinction, but Peggy, the way you put it, I, um, the deflationary effect of tech advances, now it's true. You can go find, um, there's many, many cases of this where technological advances in particular fields are bringing down prices. And people think of that as obviously deflationary, cuz it's prices coming down. And I think the feeling is, uh, aren't we living in an age where the technological advances are so great that we're enjoying productivity gains and unit cost reductions that are leaps and bounds beyond anything we've seen in the past, therefore, and here comes the logic of therefore we can get away with printing way more money.

Speaker 1 00:32:07 Uh, and maybe the M m t people would say that, um, without the deleterious effects, I don't find evidence of that. I'm not saying there hasn't been, say in the last 20 years, enormous technological advances, but there don't seem to be outsized, you know, relative to those seen in the twenties, those seen in the sixties and seventies. And it also, another test of this would be whether productivity figures are going up, a productivity for those who don't know, it isn't just production. Peggy, you know, this, it's production per hour or production per unit. And those aren't rising significantly either. Now, if they were, there would be a better argument for saying, well, if inflation, as the monetarist said is too much money chasing too few goods, can't we get away with it by producing many, many, many more goods? That's what the technological revolution's supposed to be. Well, we're just not doing that. So that that's not a way out, I don't think, that's not a way out of the explanation for how can the money supply increase so much without inflation going up.

Speaker 3 00:33:14 Well, you could argue who's getting it when, um, let's say that okay, the government is absorbing, uh, through deflation, through spending so much the benefit of the, um, deflationary effects of technology Yeah. Which also are offset, by doesn't mean we're working harder, we might be working less. Yeah. Um,

Speaker 1 00:33:38 That's right.

Speaker 3 00:33:39 Just, you know, with less effort, you produce more, so there's not as much

Speaker 1 00:33:43 Yes, that's

Speaker 3 00:33:43 A compensation there too. But the unequal benefit, if the big message is that, you know, against the 1% and the, the common man, the common man is getting sucked off of, um, while the government gets the dollars first and spends them for allocates them as they wish. And then, uh, you know, after the, the buying powers spent, you know how the dollars have been diluted into the money supply and our buying power is less than we get it. So that's another way that the printing spending m m t type thinking biases those in control against the common person.

Speaker 1 00:34:32 Yep. Um, you alluded to, I, I think, uh, the status of the dollar is a reserve currency, a very technical issue. But that is another way to explain the paradox. Uh, uh, if you have a currency, it's called the reserve currency of the world or the dominant one, it means

Speaker 3 00:34:51 Externalizing. Yeah.

Speaker 1 00:34:53 People around the world wanna hold dollars mm-hmm. <affirmative> and central banks particularly hold them in, um, their reserve. If so, notice that that would increase the demand for dollars. So, but the problem here is that the more money you issue in Britain did this around starting around World War One, the more money you issue and the less credible your money becomes, the demand for it withers away. And so there's like a double whammy. You're not only increasing the money supply a lot, you are risking and jeopardizing your role as a reserve currency, uh, because people start doubting it, uh, start doubting its value. So when the supply keeps going up, but the demand goes down, now you're, now you're risking a double digit and maybe even a hyperinflation. If the u I would say if the US keeps on the current path within 50 years, the dollar will not be the major currency of the world.

Speaker 0 00:35:43 Okay. Well, um, great. Uh, I do want to go to Dale. Dale, thanks for waiting. You think you'll have to unmute in the bottom right hand corner microphone.

Speaker 4 00:35:59 Okay, thanks. Thanks for that. Listen. Um, I feel like I'm the only one, you know, for the last like 15 years of what, with the quantitative easing and the, all the money creation and the inter the negative interest rates on the ur and you know, like we, Ben Bernanke gets the Nobel Prize in economics, <laugh>, and it's like I and I, and I feel like, am I the only one? And it that, that this is such an outrage and, uh, yeah. You know, uh, I I I even within the Liberty community, I do a lot of reading and yeah, I don't see a lot on this. So what's, what's going on here? <laugh>,

Speaker 1 00:36:41 You don't see a lot on what a critique of the monetary fiscal state Dale, is that what you mean?

Speaker 4 00:36:47 No, I, I guess just that here, we, you know, uh, we allowed, uh, all this, all this praise on, uh, you know, Ben Bernanke is this great hero, and it's like we give him the Nobel Prize and it's like, you know, I I I've not come across a lot of criticism. Yeah. This guy just a total fraud.

Speaker 1 00:37:06 Well, I, yeah, I, I I attribute this to, um, the status of central bankers. So, uh, so set aside for a moment, any particular personality, whether Greenspan or Yellen or Bernanke, and there's just an enormous apparatus. And by the way, not just at the Fed, which has its own PR department, but having worked on Wall Street for many years, I know this also is true of the big brokerage firms, the major economists at the brokerage firms, they work very closely with the Fed, uh, facilitating the underwriting of these government debts. And I've known people at JP Morgan and elsewhere who tell me that if they are critical at all of the Fed, uh, they get pun, they get punished for it. It's unbelievable. They, they get pressure. Uh, it shouldn't be unbelievable. They get pressure, uh, fr literally from treasury officials or fed officials, Julie, behind the scenes.

Speaker 1 00:38:01 And, and, and same thing, I think in testimony before Congress, many of these congressmen have no idea what they're facing. So if they're interviewing a Greenspan and he does a two-step and starts wa talking in obscure terms, they just think he's profound, you know, uh, because he's so obscure. So, uh, they're, they're insecure even in questioning these central bankers. But what it comes down to, I think, Dale, is if we have this, uh, propagate welfare state, and it absolutely needs this central bank, its goal not to promote prosperity, not to promote bank safety, I would say not even to promote financial systems stability, its goal is to finance Proative government. But you never would hear anyone from Bloomberg or cn b C or the Wall Street Journal of the Financial Times say such a thing. They, they would think, what I just said is cynical.

Speaker 1 00:38:55 They would say, no, no, no, the central bank's there to, you know, fight inflation. And I would say, no, it causes inflation. No, they're fighting inflation. And if there's a financial crisis, it's never that the Fed or the F D I C or Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, it's never that they caused it or stoked it or called moral hazard. There's some of that, you know, some of that's out there. There is criticism, but, uh, you're absolutely right that there's a almost a uniform, almost ubiquitous PR campaign to either cover up the sins of these monetary central planners. And that's what it is. Central banking is central planning applied to money and banking. And when the Soviets fell in the nineties and everyone said Capitalism one and socialism lost, why then is the money and banking system still socialized? And, and I think the theory has to be that that's how government, when it gets propagate finances itself, but very little criticism.

Speaker 1 00:39:49 You're absolutely right. Those of us who do criticize just get marginalized or ignored. It just doesn't fit the script. It doesn't fit the narrative. Um, and maybe people suspect and know that if you were critical of these institutions, what else? How else would you finance the government? They kind of know. And I, I think that of the MMT people as they read between the lines of what they say and see them advising people like Bernie Sanders, it's almost like the logic goes something like this. We want huge government that requires huge government spending. We gotta be electorally sensitive to getting voted out of offices. We raise taxes, therefore we need borrowing and money printing, and here's the final, uh, punchline <laugh>. Therefore we need a theory that says, that's okay to do and there won't be any damaging effects. Uh, it's not a very scientific way of going about it. You know, they're backing into a conclusion in order to support a burgeoning state. That's their primary goal. Their primary concern. That's too long an answer, Dale. I'm sorry.

Speaker 4 00:40:54 Well, yeah, you know, except for, except for the Atlas Society. I don't see a lot of fi the 5 0 1 <unk> <unk>. Uh, you know, I understand the institutions that you were referred to that they would be kinda scared, but, you know, I'd like to see more discussion in the five, the Libertarian 5 0 1 <unk> out there anyway. Oh, that's,

Speaker 1 00:41:11 Oh, I see what you're saying. Yeah. That's interesting. And this might, it, it might interest you that, uh, there was a period many years back when I was coming out of graduate school where instead of going into academia with my degree, I was considering, uh, public policy think tanks in Washington. And I visited all the usual suspects, including Heritage and Cato and ai, the, the right wing, if you will, right wing oriented. And I found something very interesting since my specialty was public finance, and specifically a knowledge of central banking and yield curve. All the things you mentioned, all the things we're talking about today, many of them said, we don't need, um, uh, we don't have a group that does that. We have a group that does taxes. We have a group that does spending, we have a group that analyzes regulations, you know, so they'll do white papers and they'll appear on, on the hill and they'll testify, but, but we don't have a critique of the Federal Reserve or monetary policy.

Speaker 1 00:42:05 And I said, why not? Or, uh, and they said, because it's so established an institution, and we've been off the gold standard so long that it's futile. Now this is from free market, um, public policy think tanks. Uh, that was a head shaker to me. I had not have thought of it that way. Um, John Allison, when he was at Cado to his great credit, started a group called, uh, the Center for Monetary Alternatives where, and George Sgin, uh, headed it for a while where the goal was to keep alive at least some discussion of the gold standard, a federal re even a federal reserve on the gold standard. Some kind of monetary rule if it, even if it was a Freedman monitors rule. And, um, and, but they, you know, they get very little traction because it's not, uh, it's not an issue, it's not a debate in Congress as to whether to have a central bank, of course, you know, uh, let alone what kind of rules it should adopt.

Speaker 1 00:43:04 It's totally rule less. Now we're being, we're being ruled by monetary rulers who've jettisoned all rules. There's not, there's no gold standard rule, there's no money supply increase rule. There have been like four or five. Taylor rule is another one. There have been four or five, uh, quote unquote rules suggested over the years by economists who are trying to make central banks behave. And it's just never successful. And, and my theory would explain this because if the goal of central banking is to finance profit of government, they don't want any rules to handcuff themselves, if you will.

Speaker 0 00:43:40 Alright. Um, well, we've got a few people that have come up. We'll try to get them in the last, uh, you know, 15 minutes or so. Um, let's start with, uh, David Kelly, you may have to talk loudly for us to hear you with your sound issues.

Speaker 5 00:43:56 Okay. Uh, can, is, can you hear me now?

Speaker 0 00:43:59 I'm barely, go ahead.

Speaker 5 00:44:02 Okay. Um, Richard, uh, you know, I'm, I, a lot of what you're saying is over my head. Uh, I'm, I've tried to learn what I can about e economics, but financial economics is, you know, the, the, uh, my,

Speaker 0 00:44:20 It's tough to hear you. I would just go for the question.

Speaker 5 00:44:23 Alright. So I want to go back to something Richard, you said about philosophy and, um, culture and economics. Um, and, and that is, do you see influence of post-modern thought in philosophy and, uh, in the culture at large on, in influence Or, or, or, um, does it it in some way enable or help the, um, MMT philosophy that you're talking about?

Speaker 0 00:44:59 Did you get that, Richard?

Speaker 1 00:45:03 I did. And, um, how would I put it, David, you know that in concept formation, there's a theory called nominalism nominal coming from name, and the idea is concepts are just names. We give things arbitrarily, giving them names. They don't have any necessary tie to concretes in the, the way the objectives would reduce concepts to concretes and sensation, things like that. I think, I think what MMT is, is monetary nominalism. It literally is the idea that government issued the money, therefore it's valuable. Uh, we can just name whatever. I mean.

Speaker 0 00:45:42 Oh, Richard, good. You're back.

Speaker 1 00:45:44 Was I out? Was I out for a minute there? I guess. Yeah, I guess I hit something wrong.

Speaker 0 00:45:49 Yeah, so we actually, uh, David, if you wouldn't mind, uh, re-asking your question, uh, burn Bone. Did,

Speaker 1 00:45:55 Did you? Okay.

Speaker 0 00:45:57 We heard most of your answer, I think.

Speaker 1 00:45:59 Okay. Okay. So is there another question? Okay, go ahead.

Speaker 6 00:46:05 Yeah, so my question was building off of Peggy's talking about the impacts of technology on, um, modern economic thinking, and I guess also what's been going on in the economy, but it was related to the growth of what I heard to referred to as the service economy. Yeah. Um, and just as lots of jobs and a large portion of the economy became service based. Yeah. Um, as long as there's more money flowing and like I can now get $80 for, if I'm a massage therapist, whether I'm charging $80 or a hundred dollars or $200, yeah. If there's inflation and more money supply doesn't matter as much because it's just a consistent flow of money from person to person, not through businesses, not through production, um, enterprises, um, and traditional crea and traditional wealth creation, uh, metrics, I guess. So I'm wondering if that's in impacted the system or if that's impacted thinking in a similar manner, uh, to how technology can do that.

Speaker 1 00:47:11 I've heard that theory, uh, David, but I don't endorse it. Um, the trend, especially in the US but elsewhere as well. The trend torn an economy shifting from say, away from agriculture, manufacturing jobs and employment to service is, is a long term, what they call secular trend. It's not cyclical, it's not up and down. And so there's, there's almost no correlation between that and the kind of numbers we're talking about inflation and other things. So I don't, I don't subscribe to that idea. It is true productivity-wise, by the way, that it's harder to measure productivity in the service sector. So some people do argue that the productivity numbers I cited, namely, well, productivity has not been increasing much is due to this service sector, uh, shift. That may be true, but even those numbers aren't, uh, back to Peggy's point, the, uh, that doesn't explain why you can have a cascade of money and no higher inflation.

Speaker 1 00:48:06 The productivity numbers may be understated a bit, but they're not so understated that they can offset this cascade. And let's understand what the cascade is. I mean, the Federal Reserve balance sheet, I think today is something like 8 trillion. It was 800 billion in 2008, so it's gone up 10 times since 2008. And the money supply today, M two, the last time I checked was something like five or, uh, do I have the numbers? A 17 trillion or so that's double, but it was 10 years ago. Something like, so these numbers are off the charts and, uh, all else equal a two or 3% productivity gain wouldn't be able to offset this.

Speaker 6 00:48:45 Would you mind if I push back slightly? Sure. Um, so if, if 2008 there was 800 billion and now there's 8 trillion, um, that's a lot of money being spent in my understanding. Unless there's been a massive amount of consumption of traditional goods or, um, Americans just eating a massive amount of food, <laugh>, where is that money going?

Speaker 1 00:49:11 Why do, oh, that's, yeah. Oh, that's a good question. Cause my, yeah, my earlier, my earlier theory David, was people are just hoarding this cash and these securities and that you can measure. I, I, when I first thought of this, I thought, well, I need to go find out measures of this and those, you can get, uh, some of the numbers are sketchy, but you can see that people, corporations, households, and others are holding an enormous amounts of cash in their bank accounts unused. So there is hoarding going on. That would be the inflation part of it. And then the other thing is, uh, TBIs and T bonds. Yeah. So David, yeah,

Speaker 6 00:49:50 Go ahead. Thank you.

Speaker 1 00:49:52 Yeah. Okay.

Speaker 0 00:49:52 Yeah, I just wanna try to get, uh, Carl and Tom in Carl.

Speaker 1 00:49:56 Okay.

Speaker 7 00:49:58 Um, hi. I joined the, uh, thread late, so I don't know, did any, did was any of the discussion not on the endless effects of, of money debasement, but, uh, but actually on the fundamental precepts of people like Stephanie Kelton who advance, uh, magic monetary theory as some kind of a solution?

Speaker 1 00:50:18 Yeah, we did talk, so we did talk about that. You did? Yeah. Alright.

Speaker 7 00:50:22 Um, my, my point is when I listen to Stephanie Kelton, Michael Hudson, other people like this talking about it, yeah. They always give us examples and they, they use the word scholarly. There's been a lot of scholarship done, but it's always a kindergarten level analysis, and they make mistakes. The moment you go one level deep beyond what they advance, the, their whole theory falls apart. Uh, their whole, the whole foundation for their system explodes. If you've already done it, then I don't have to bother, then I'll just, uh, I'll mute off and, uh, uh, listen to the other commentators.

Speaker 1 00:50:57 Great, thanks.

Speaker 0 00:50:59 Yeah. And you can go back and listen to a replay for what he said, uh, specifically about Stephanie earlier. Tom, thanks for waiting.

Speaker 8 00:51:08 Uh, hello. Hello. Uh, I wanna ask you about the connection between those huge infrastructural projects, which costs, uh, a lot of money. And those, uh, projects, it is explained, wouldn't be possible without, uh, this monetary policy, which is connected with, uh, great, uh, loans and, uh, emitting, uh, some, uh, papers. And, uh, it is a kind of escape, I think, from the market because, uh, some people are explaining that those projects wouldn't be feasible, uh, without, uh, this huge loans. What do you think about, is it really, uh, important and is it really, uh, reality explanation that this infrastructural projects wouldn't be possible, like, you know, travel to Mars and some things like

Speaker 1 00:52:11 That? Yeah, I get the, the answer is no. Uh, if the government was spending on, uh, actual tangible infrastructure like airports and tunnels and bridges and roads and things like that, uh, the, the power grid, very, very important. That would be a whole nother thing. We could still debate whether the government should be doing that, but that's not transfer, that's not robbing Peter to pay Paul. That's not just transferring income wise. That would actually add, uh, possibly to the productive prowess of the economy. That's not why they're printing money and borrowing money. The, the infrastructure projects today are mostly transfer. They aren't, uh, investments in these tangibles. There is a eroding of the underlying US infrastructure based, uh, due to the fact that we've shifted to redistributing wealth instead of creating wealth. So there is something that might interest you. I wrote in a whole chapter on this.

Speaker 1 00:53:01 There's something called the Golden Rule of Public Finance, which said that it's not necessarily bad for the government to borrow if it's borrowing for, um, long-term projects that would enhance the productive prowess of the economy. And you might even argue that, uh, fighting a war and getting rid of, uh, Hitler, uh, is a long-term investment as well, or when Reagan borrowed for sdi and the end result was getting rid of the Soviet Union and having a Cold War. But notice that those are long-term benefits, uh, where the debt, uh, seems justified because it's gonna be easily paid back with future productive prowess. That's not what's going on today, sadly enough that the government's spending, uh, on infrastructure relative to total spending has shrunk with every passing here.

Speaker 0 00:53:49 Great. Um, well, uh, yeah, I, um, I'm thrilled. We had a lot of people asking questions. I had some others about, uh, you know, your comments about reducing the, the tax base to kind of, uh, get those people out of power as a motive of that. But, uh, we, we can, uh, we, we could actually do another whole topic on, on something related to this.

Speaker 1 00:54:19 Yeah, I think, uh, uh, it's a, a fiscal illusion, which I refer to, we're stopping at seven, right, Scott?

Speaker 0 00:54:25 Yeah. I, um, I didn't know if you, uh, you know, for the, when you dropped off, but you can go ahead and summarize real quick and

Speaker 1 00:54:33 Yeah, well, some Okay. Summarizing quickly. Uh, MMT is a kind of rationalization and justification of the two components of government finance, which are least visible to people and voters, namely borrowing money and printing money. It's a way of financing government other than taxation, which the people are really, uh, pushing the, their, uh, goal, I believe. Uh, and the fact that Bernie Sanders and others are their best clients is to have gargantuan government much bigger than we already have. And it's grown enormously in the last couple of decades. And they know on the other hand that, uh, going to voters and saying, well, you're gonna tax you for all this is an electoral loser. So they need a theory to justify a really, uh, exorbitant, reckless spending, uh, printing of money and borrowing of money. And I think I would say to now, they've been able to get away with it because we have not yet seen the kind of higher inflation and higher interest rates seen, at least in the seventies.

Speaker 1 00:55:34 I believe a lot of that in the seventies was due to going off the gold standard and the shock of it. Uh, but the US is, uh, perfectly, uh, able to return to double digit inflation and double digit interest rates over the coming decade, uh, if it continues to doing what it's doing. Funny enough, the MMT people when asked, well, what are the limits? Are there any upper limits to money creation in debt? And they'll say, well, when we see inflation going up and when we see interest rates going up, then we'll realize it's too much. Well, if you've already poured all this stuff into the system, uh, very hard to take it back, um, then it's gonna be too late. And then of course, they'll be laughed off the stage and it'll be too late. Everyone will say, oh my God, why did we listen to those MMT people all those years?

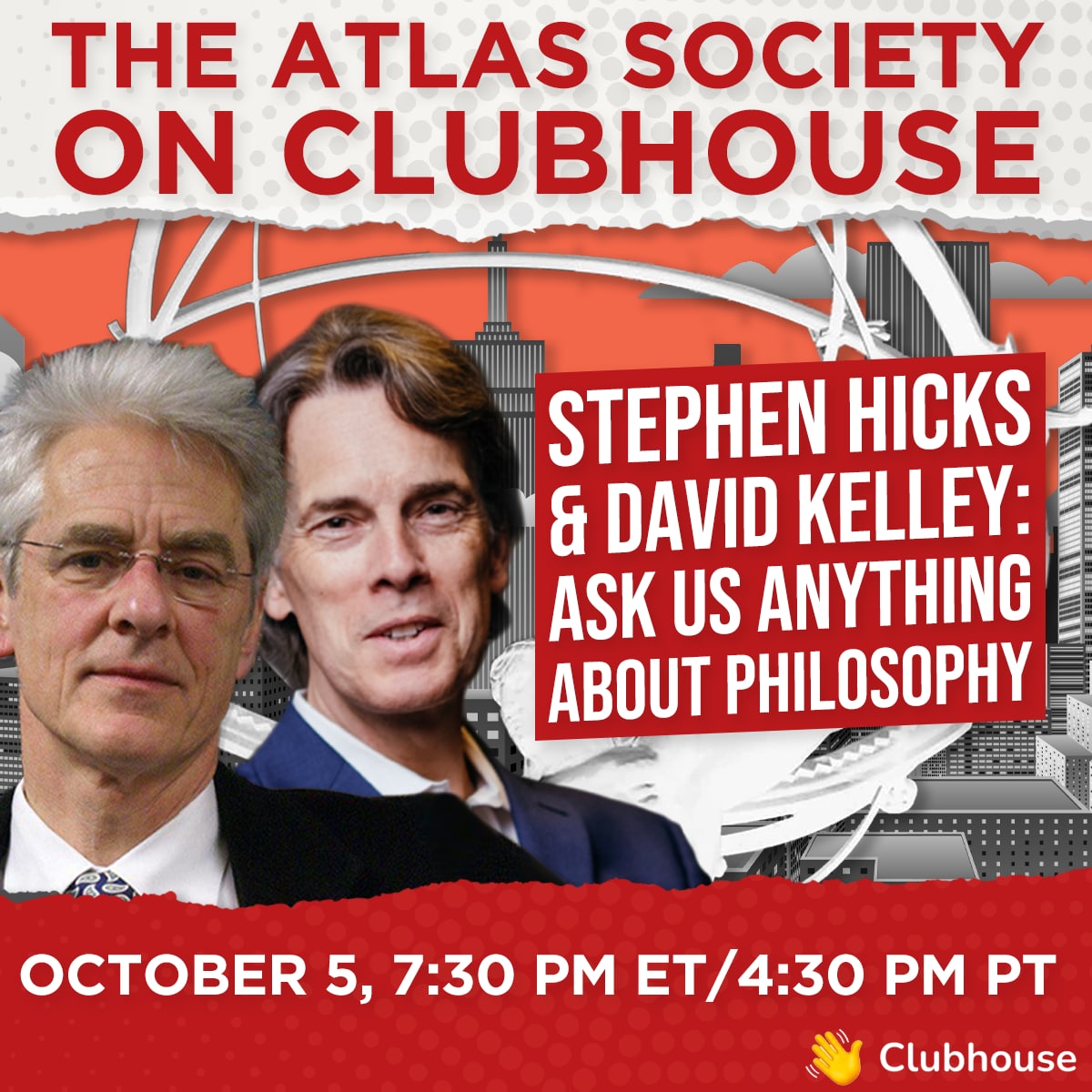

Speaker 0 00:56:19 <laugh> the big crashes, our signal to change. Well, this has been, uh, a great session. Thank you so much. Um, next, uh, Wednesday, the Atlas Society asks Paul Johnson at 5:30 PM Eastern. Then at 6:30 PM back on Clubhouse, we'll have Steven Hicks and David Kelly doing an ask us anything on philosophy. Should be a great one, and we hope to see you there again. Um, we are the Atlas Society. Uh, you can follow the link, uh, atlas society.org and we appreciate everyone's support and participation. Take care. Thank you, Richard. Thank you, Scott. Thank you everyone.